The Way We Remember

Fritz Koenig’s Sphere, the Trauma of 9/11, and the Politics of Memory

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of 9/11 and responding to a vibrant popular and academic debate about the role and function of public monuments The Way We Remember: Koenig’s Sphere, The Trauma of 9/11 and the Politics of Memory explores three distinct but interrelated themes surrounding the issues of public monuments; memory, trauma, postmemory; and the power of art to represent the past.

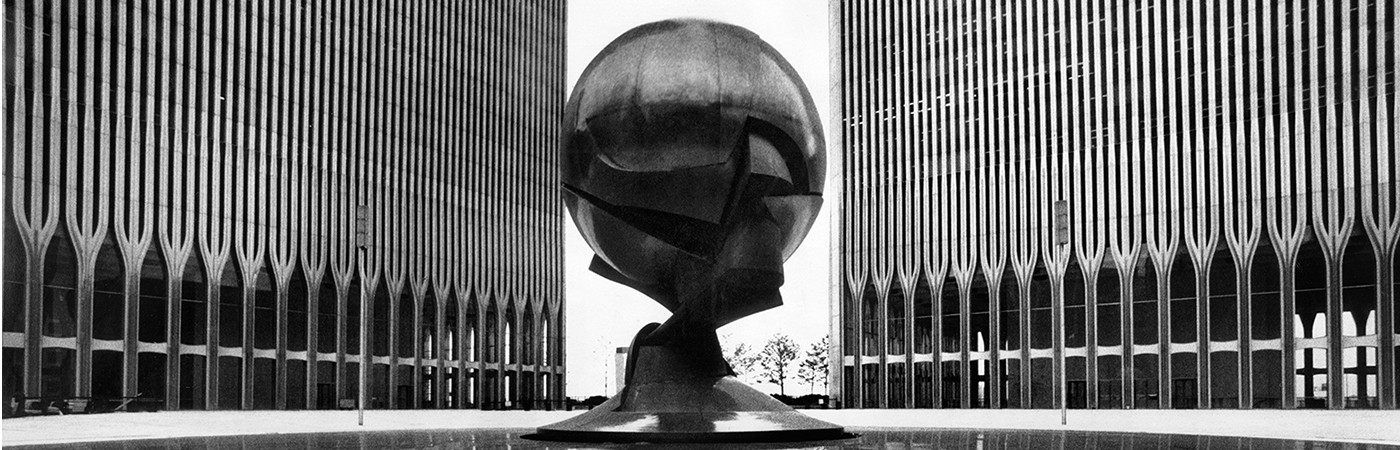

The Way We Remember opens with a focused examination of the German modernist sculptor Fritz Koenig’s Great Caryatid Sphere (1968–1972), which was originally created as a fountainhead and monumental centerpiece for the World Trade Center Plaza and became one of the earliest memorials of 9/11 after it emerged from the rubble of the collapsed Twin Towers—battered, bent, and scarred, but resilient and defiant in still standing upright where it was once placed between the now-collapsed twin towers.

The Sphere provides a unique entry point for the exhibition section that tells the story of 9/11 through the lens of its first “unofficial” memorial, and the debates that resulted from the implementation of the World Trade Center memorial project and the inauguration of “Reflecting Absence” as an official National 9/11 Memorial.

Beginning in the early 1960s through the early 1990s Koenig worked on many commissions and projects that memorialized the victims of persecution against Jews. Brought together for the exhibition the works and archival materials for these works tell a story of European, and especially German post-war memorials and the "memory-work" they perform.

On Columbia University’s Morningside campus, students, faculty, and staff have gathered annually on College Walk to commemorate those who lost their lives on 9/11, among them 42 Columbians, by reading their names aloud and placing US flags, one for each life lost, on adjacent lawns in a recurring effort to visualize the enormity of our collective loss. While these annual 9/11 commemorations are ephemeral, Columbia’s Morningside campus is dotted with other, more permanent markers of memory in the guise of monuments erected since the University moved to Morningside Heights.

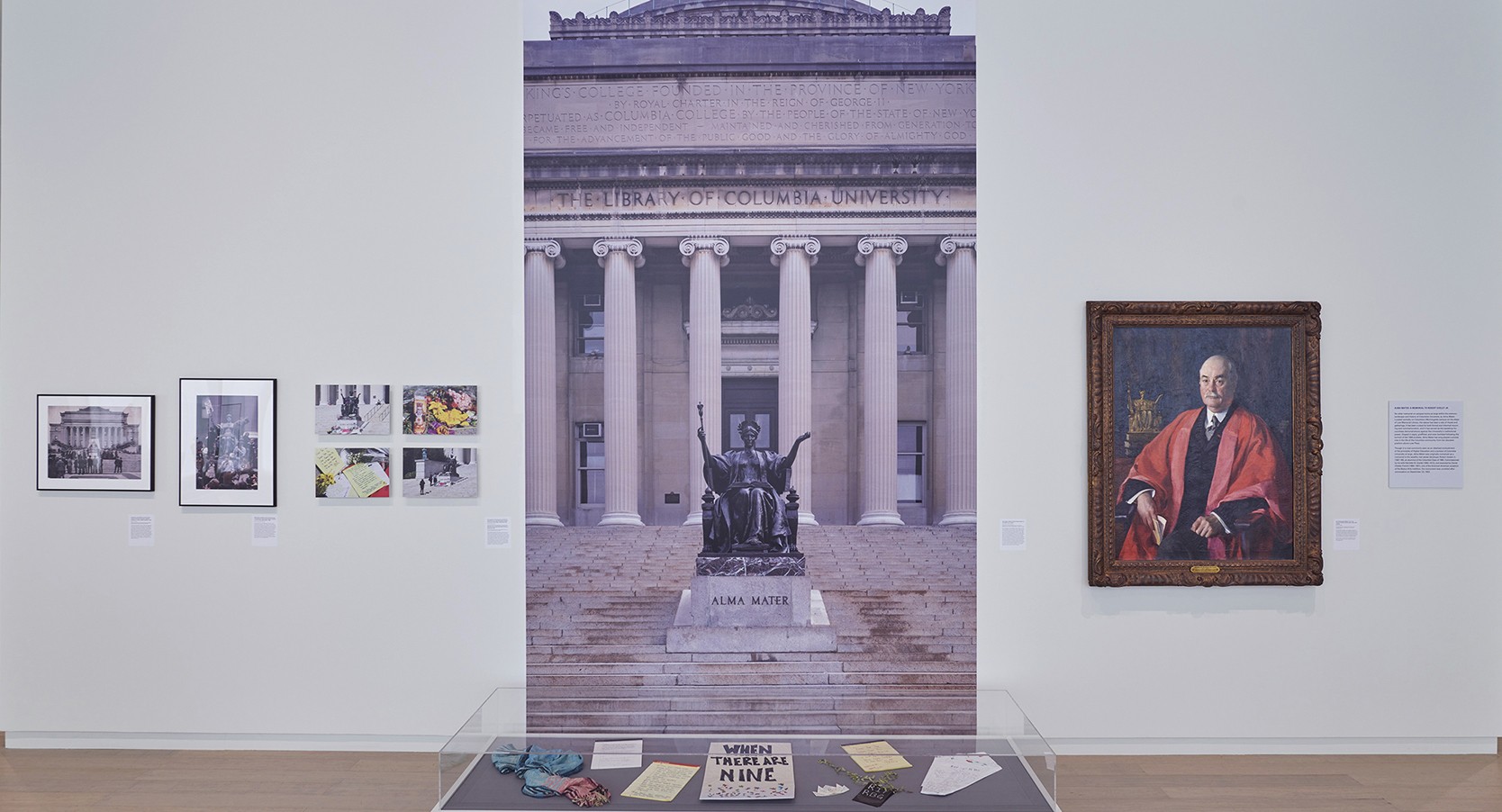

Featured in this section is Daniel Chester French’s statue of Alma Mater (1900–03) which stands prominently as a physical embodiment of the Columbia community. Commissioned by Harriet Goelet as a monument for and memorial to her recently deceased husband and Columbia alumnus Robert Goelet Jr. (1841–99), the statue continues to attract student attention in times of crisis and mourning and has been the focus of student activism, and sometimes violent protests: on May 14, 1970, for instance, three sticks of dynamite ripped a hole into her bronze garments. But Alma Mater is also the center for make-shift memorials, most recently following the death of former Columbia Professor and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Other campus monuments featured in this section of the exhibition are William Ordway Partridge’s statues of Alexander Hamilton (1907), Thomas Jefferson (1914), and College Dean John Howard van Amringe (1911–22) allowing for an exploration of different memorial modes, strategies of display, and an investigation of changing attitudes, both peaceful and violent, towards the campus monuments and those who they were set up to commemorate.

Twenty years after the attacks on the World Trade Center we find ourselves in the middle of a global public health crisis of unprecedented proportions. At the height of the pandemic in December of 2020, the daily death toll in the United States surpassed for the first time that of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on every single day.

How do we begin to visualize or quantify the enormous loss in human lives and make it palpable? How do we mourn and commemorate those we have lost? Is there an appropriate way to memorialize this moment of individual and collective suffering in the history of our nation, especially in local minority and immigrant communities, which were hardest hit by the pandemic across the country? Do our memorial traditions provide us with appropriate forms of commemoration? Can artists’ responses to previous traumatic events such as the First and Second World Wars, the horrors of the Holocaust, or the events of 9/11 provide us with viable models? In order to explore these questions, we reached out to artists and members of our local communities in and beyond Morningside Heights to invite proposals for memorial projects that will be presented in this section of the exhibition. Their responses will offer preliminary insights and possible answers.

Participating artists in this final section of the exhibition include Cathleen Campbell, Delano Dunn, Dianne Smith, Jonathan Calm, and Nyssa Chow.

INSTALLATION VIEWS

Image Carousel with 21 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell

-

Slide 2: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 3: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 4: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 5: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 6: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 7: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 8: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 9: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 10: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 11: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 12: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 13: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 14: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 15: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 16: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 17: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 18: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 19: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 20: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

-

Slide 21: Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.

Installation view of the exhibition "The Way We Remember", on view at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University September 10-November 13, 2021. Photograph by Kyle Knodell.