Living in America: Frank Lloyd Wright, Harlem and Modern Housing

“Living in America,” a phrase written on wooden panels traveling with the model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City (1929–58), evokes a question that preoccupied architects and planners throughout the mid-twentieth century: How to live together? Wright’s proposal for an exurban settlement of single-family houses offered one possible answer; plans for large public or subsidized housing located in urban areas presented another. Although these two visions seem a world apart, they share a common history.

SELECTED WORKS

Image Carousel with 4 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Mattie Faulkner and her children moving in, Riverton Houses, July 29, 1947, Photographs & Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

-

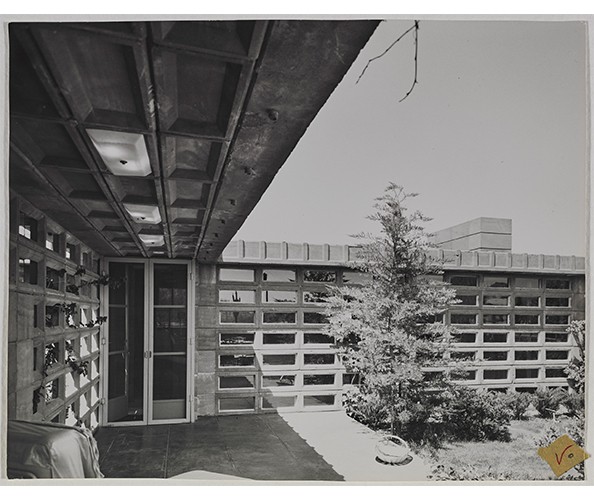

Slide 2: View of Benjamin Adelman House, 1951, The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

-

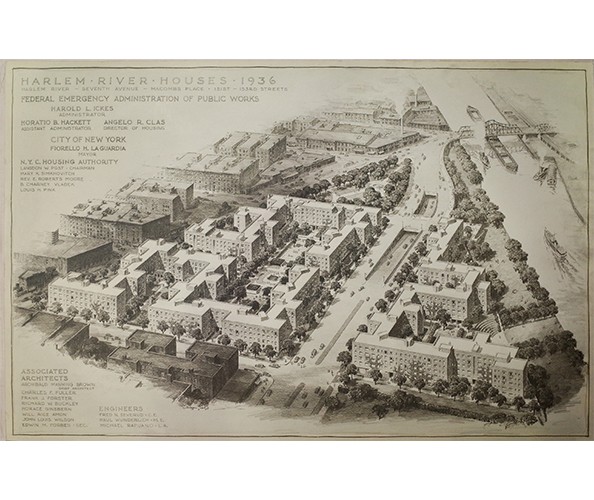

Slide 3: Perspective Rendering of Harlem River Houses, 1936-1937. Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York.

-

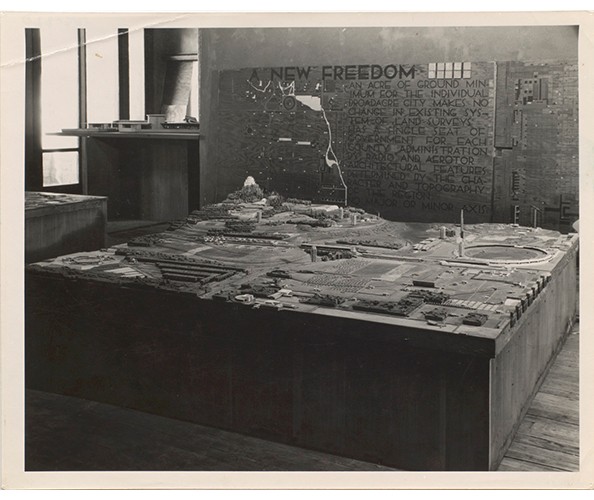

Slide 4: The Broadacre City Model, Section B, 1935. Photo by Roy E. Petersen. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Mattie Faulkner and her children moving in, Riverton Houses, July 29, 1947, Photographs & Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

View of Benjamin Adelman House, 1951, The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Perspective Rendering of Harlem River Houses, 1936-1937. Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York.

The Broadacre City Model, Section B, 1935. Photo by Roy E. Petersen. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Wright (1867–1959) first exhibited his Broadacre City project at Rockefeller Center in Midtown Manhattan in 1935. While the prominent Wisconsin-based architect anticipated a degree of economic diversity, Broadacre’s residents were, for the most part, implicitly white. In 1936 construction began on one of New York City’s first public housing developments, the Harlem River Houses, funded by the Public Works Administration under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Built for working-class African Americans, the complex was designed by a consortium including John Louis Wilson Jr., the first African American to graduate from Columbia University’s School of Architecture. Through such parallel examples, this exhibition shows how two different approaches to housing combine societal aspiration with racial segregation and socioeconomic inequality, and asks: How to live in America, together?

The exhibition’s narrative takes the form of two interwoven plotlines, developed through displays of project-specific drawings, photographs, and other material dating from the late 1920s to the late 1950s. One plotline tracks the Broadacre scheme as it plays out in Wright’s subsequent work, scattered around the country; the other tracks the development of public housing in Upper Manhattan’s Harlem neighborhood, ending just outside the gallery, adjacent to Columbia’s new campus. Both stories connect social institutions, such as the nuclear family, with economic structures, such as private property or its alternatives. Wright’s version of the “American Dream” and Harlem’s public housing both draw lines of race, class, and gender, many of which persist today. Their differences remind us that the right to housing once defined, and could still define, what it means to live in America.

The exhibition is presented in correlation with Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from June 12 through October 1, 2017. “Broad Acres and Narrow Lots,” an associated essay by David Smiley, Assistant Director of the Urban Design Program at Columbia GSAPP, is included in the MoMA exhibition catalogue. Living in America’s curatorial team is composed of students from various Columbia University masters and doctoral programs together with the Center staff and in close collaboration with archivists from the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts library and other institutions.